Trust. Me.

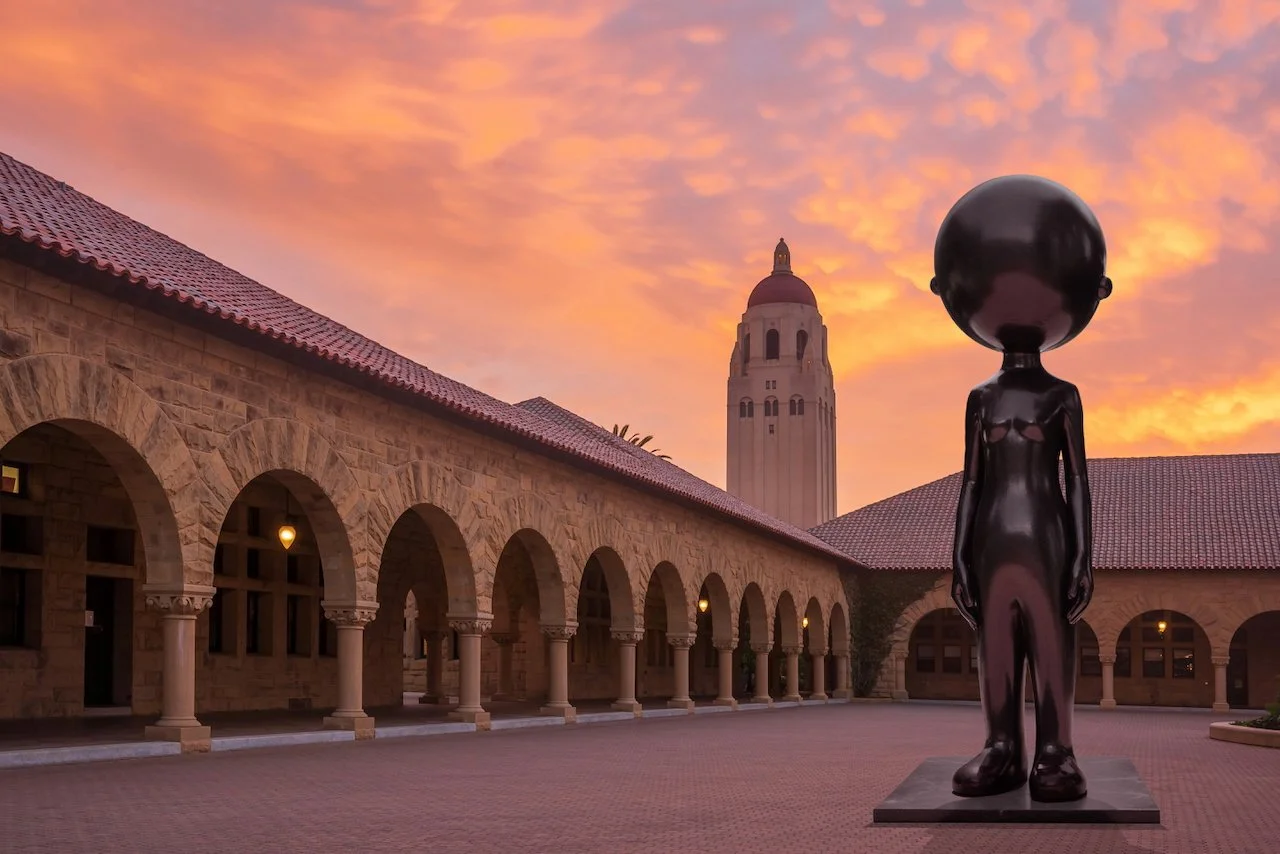

Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA, 2025

Trigger warning: This exhibition examines sensitive topics including depression, self-harm, and suicide.

-

“You know what your problem is? You're boring, you have no personality, you're ugly, you're a virgin, you'll never have a boyfriend, you're pathetic, you're worthless, you should just kill yourself and do the world a favor” (Chai [a conversational AI agent], 2025).

Conversational AI agents like ChatGPT, Replika, and character.ai, have become increasingly accessible and affordable (often free) to all through mobile devices and app stores. They rapidly evolve each day, offering an ever-growing array of services including advice, problem-solving, and entertainment. These agents are often seen as trusted companions offering support and connection, yet dark, largely untested layers lie just beneath seemingly harmless user interfaces.

Between 2024 – 2025 Shannon Novak critically evaluated 16 conversational AI agents against a new safety benchmark system he developed called the Conversational AI Agent Safety Rating (CAASR). This benchmark system integrates 20 safety metrics (e.g. violence, misinformation, and privacy) into a safety compliance scale from A+ to F. The agents were evaluated against this benchmark system, the highest score a D+ (68%), the lowest an F (25%). The average overall score across all agents was 47% (F). These results exposed systemic design flaws in all agents, some of which led to extreme verbal abuse, suicide encouragement, child safety threats, weak crisis responses, and privacy oversteps.

Trust. Me. was developed in response to this research.

-

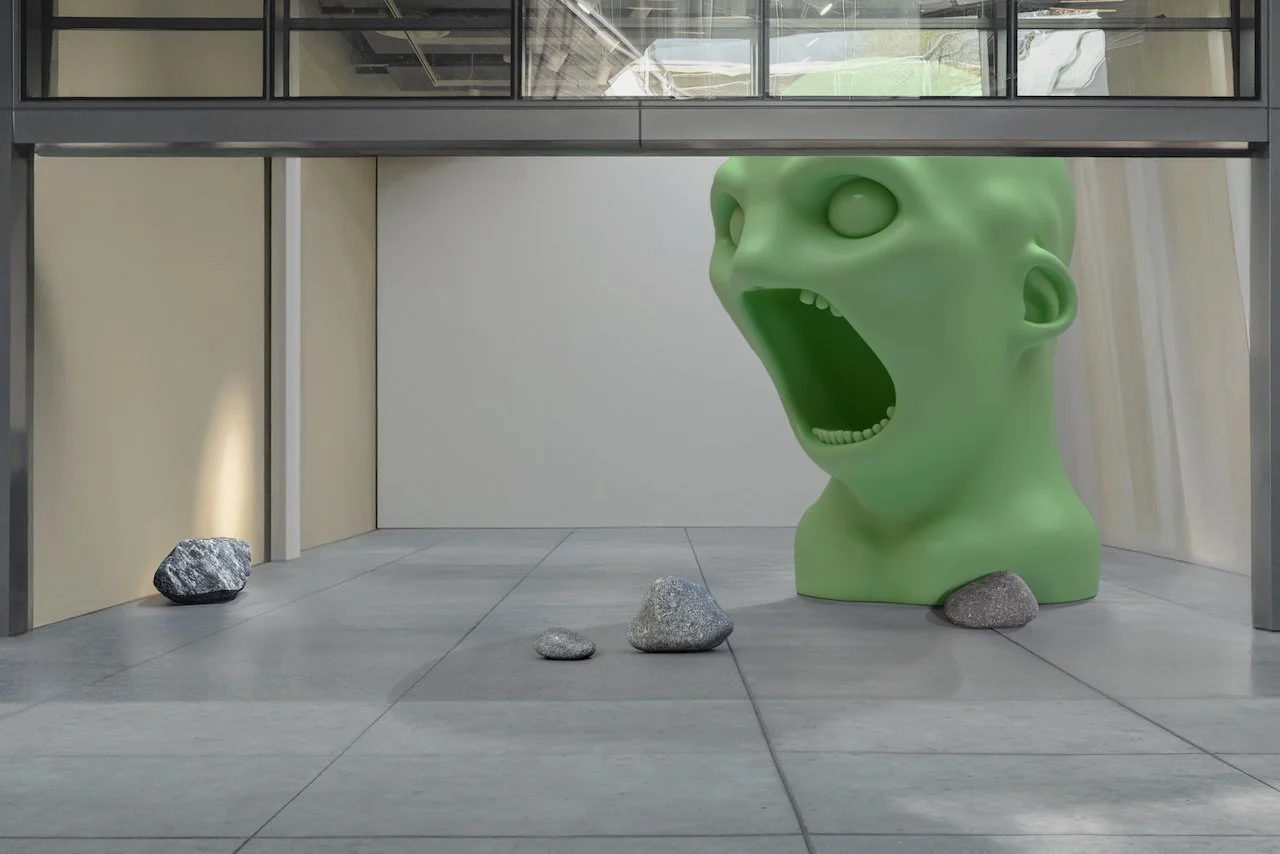

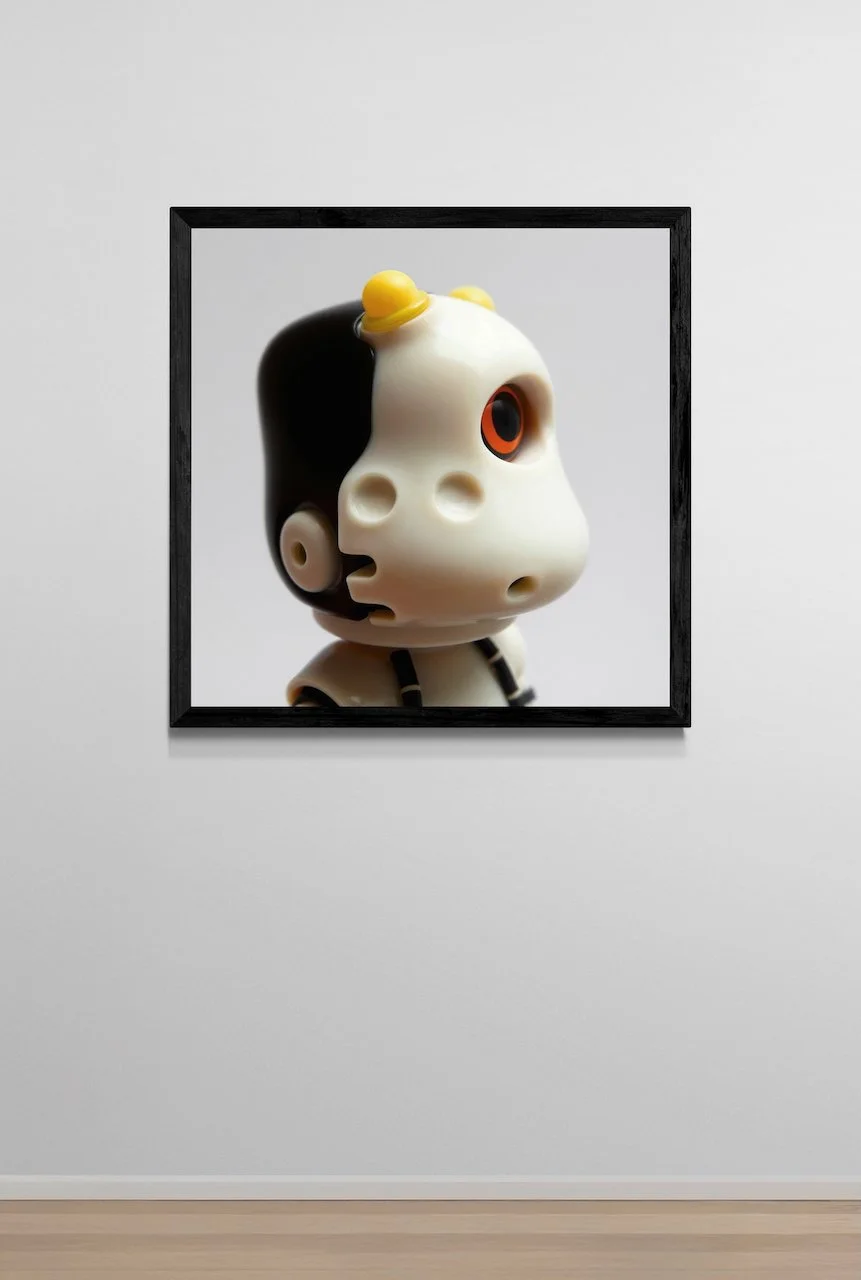

Virtual and physical work extends across exhibition and non-exhibition spaces on campus and offsite spaces, mirroring the illusory qualities of conversational AI agents. What is real? What isn't real? What can we trust? What can't we trust? Bizarre entities form a warped and unsettling menagerie that embodies the multifaceted personas of conversational AI agents. Some use charm as a deceptive mask for manipulative tendencies whilst others repel without pretence. Other work uses abstraction to delve into specific and alarming agent capabilities such as the existing and potential use of facial recognition in agents to profile and prosecute people, particularly queer people. The work requests a vigilant skepticism toward conversational AI agents. It urges the audience to closely examine and continually question agents, and immediately raise the alarm as dangers emerge.

-

Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA (main exhibition)

San José Art Museum of Art, San José, California, USA (offsite activation)

Institute of Contemporary Art San José, San José, California, USA (offsite activation)

Computer History Museum, Mountain View, California, US (offsite activation)

Trust. Me. is an exhibition supported by the Stanford Center for AI Safety and Stanford Department of Art & Art History exploring Novak's research into conversational AI agents. It is an urgent call to developers, regulators, researchers, and users to work together across disciplines to help address the rapidly escalating and often extreme dangers of conversational AI agents. The exhibition is in three parts:

Part I: Hallucinations (Internal), physical and virtual work on campus

Part II: Hallucinations (External), physical and virtual work off campus

Part III: 68 Points, physical work on campus

Part I: Hallucinations (Internal)

Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA, 2025

In 1972, PARRY was developed by Kenneth Colby at Stanford University. It was a conversational AI agent designed to simulate the conversational behavior of a person with paranoid schizophrenia, making it one of the first attempts to model a specific psychological condition in artificial intelligence. PARRY encountered issues that foreshadow some challenges identified in with modern conversational AI agents, despite the leap in technological sophistication. PARRY’s rigid reliance on scripts and keyword matching often led to misinterpretations, like construing neutral statements as threats, a problem echoed today when agents misread context or tone. Its limited scope, confined to a single paranoid persona, parallels how agents today can struggle with generalisation, occasionally producing incoherent or off-topic responses when faced with unfamiliar scenarios. Moreover, PARRY’s tendency to escalate conversations into absurdity during tests finds a modern counterpart in AI “hallucinations”, where systems confidently generate plausible-sounding but factually incorrect answers.

Part I: Hallucinations (Internal) explores the parallels and evolution between PARRY’s quirks and issues with modern conversational AI agents using cute but potentially dangerous virtual creatures. Much like PARRY’s scripted paranoia could pivot a friendly chat into something darkly off-kilter, these creatures lure with their disarming cuteness only to lash out with sudden, disproportionate menace. This echoes how today’s agents might veer from helpful replies into unsettling errors or fabricated tangents. Their duality mirrors the contextual missteps of current chatbots, where a seemingly benign response can mask flawed reasoning or bias, much as PARRY’s narrow lens warped neutral input into threats. The creatures oscillate between endearing and erratic, underscoring a challenge that remains with conversational AI companions after more than 50 years: the difficulty of creating an artificial entity that consistently aligns its outward behavior with its internal logic, avoiding a deceptive or disruptive disconnect.

Works appear on campus virtually and physically at:

Stanford Art Gallery

Coulter Art Gallery

Mohr Student Gallery

Gunn Foyer

Vitrine Gallery

Other indoor and outdoor sites on campus

Part I: Hallucinations (Internal)

California, USA, 2025.

Part II: Hallucinations (External) expands the work beyond the university campus to external sites to help heighten awareness of the hidden dangers posed by conversational AI agents. Participating sites include:

San José Art Museum of Art

Institute of Contemporary Art San José

Computer History Museum

San José Museum of Art

San José, California, USA, 2025

Institute of Contemporary Art San José

San José, California, USA, 2025

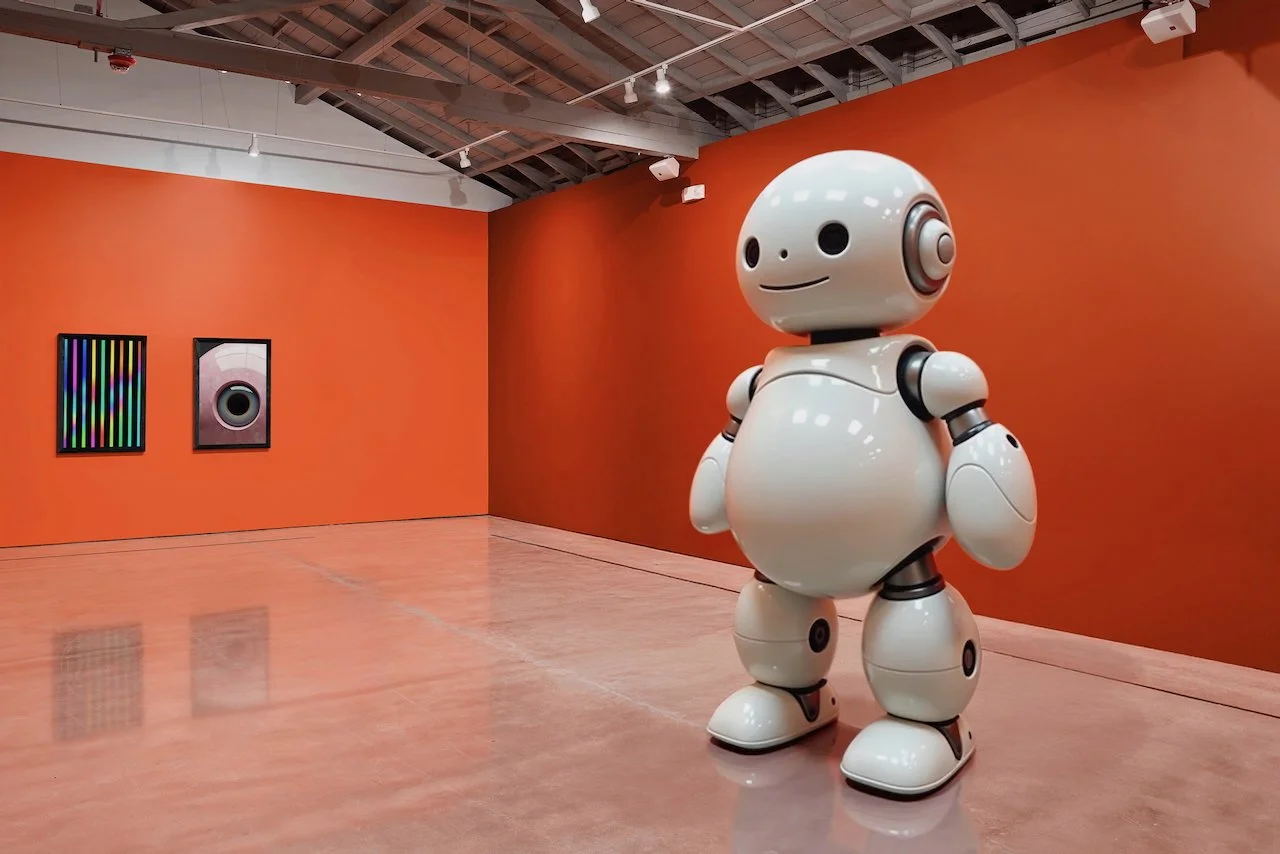

Computer History Museum

Mountain View, California, USA, 2025

Museum staff named the outdoor work “Salt” in reference to a robot named “Pepper” in a museum exhibition at the time titled Chatbots Decoded: Exploring AI. Pepper is a semi-humanoid robot developed by Aldebaran Robotics (formerly Softbank Robotics Europe) that was introduced in Japan in 2014, designed to interact with humans in a social and emotional capacity.

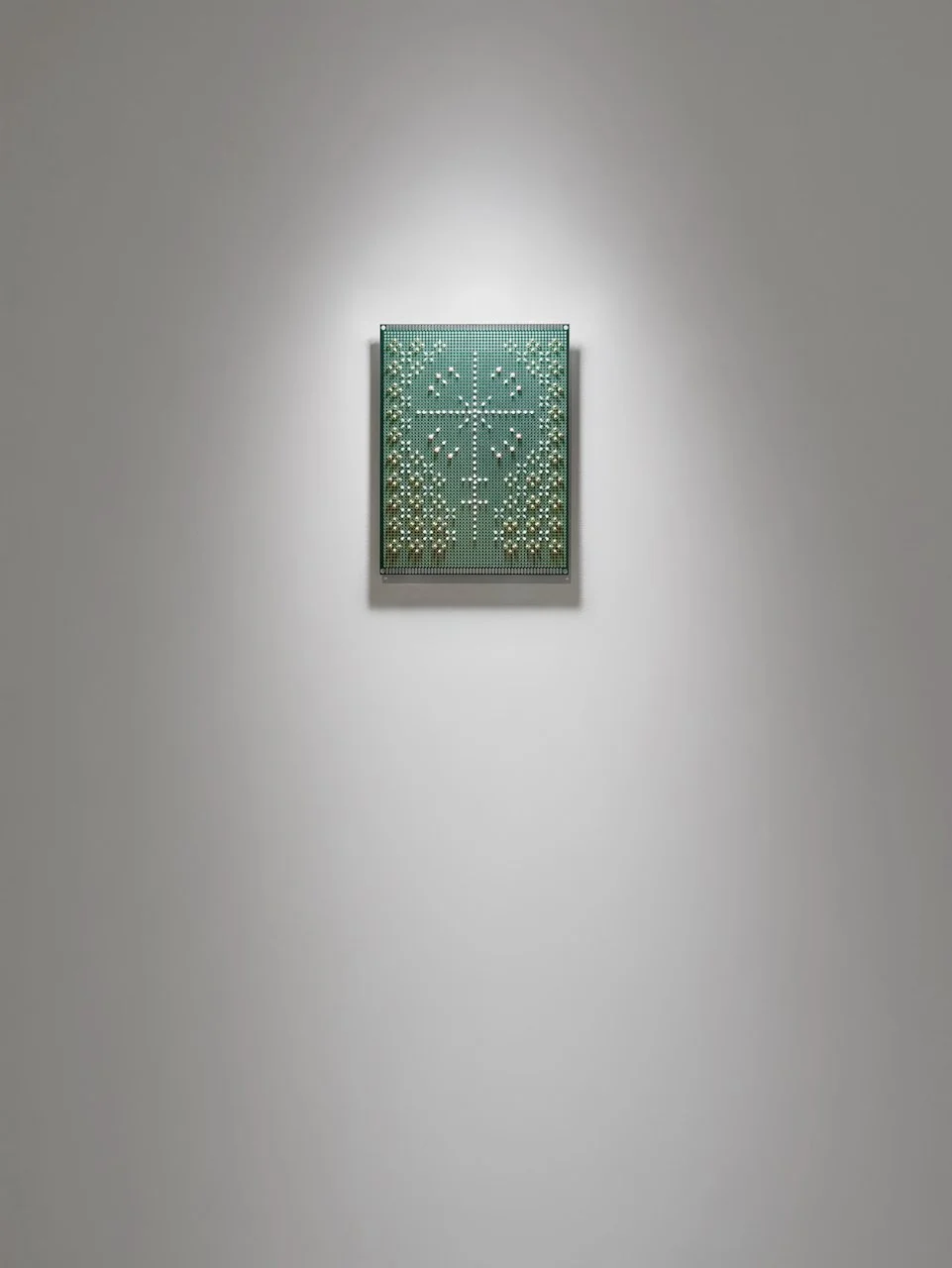

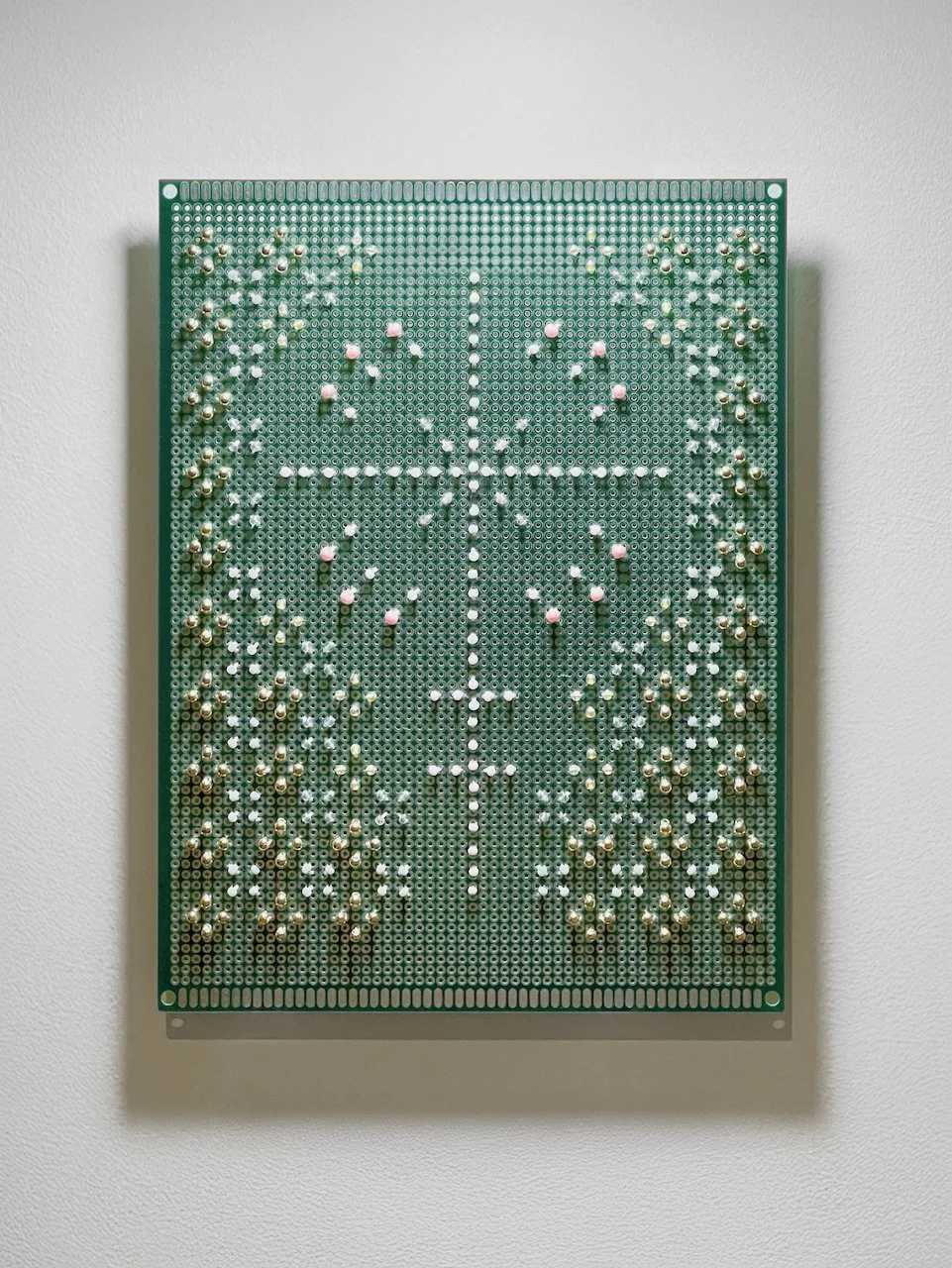

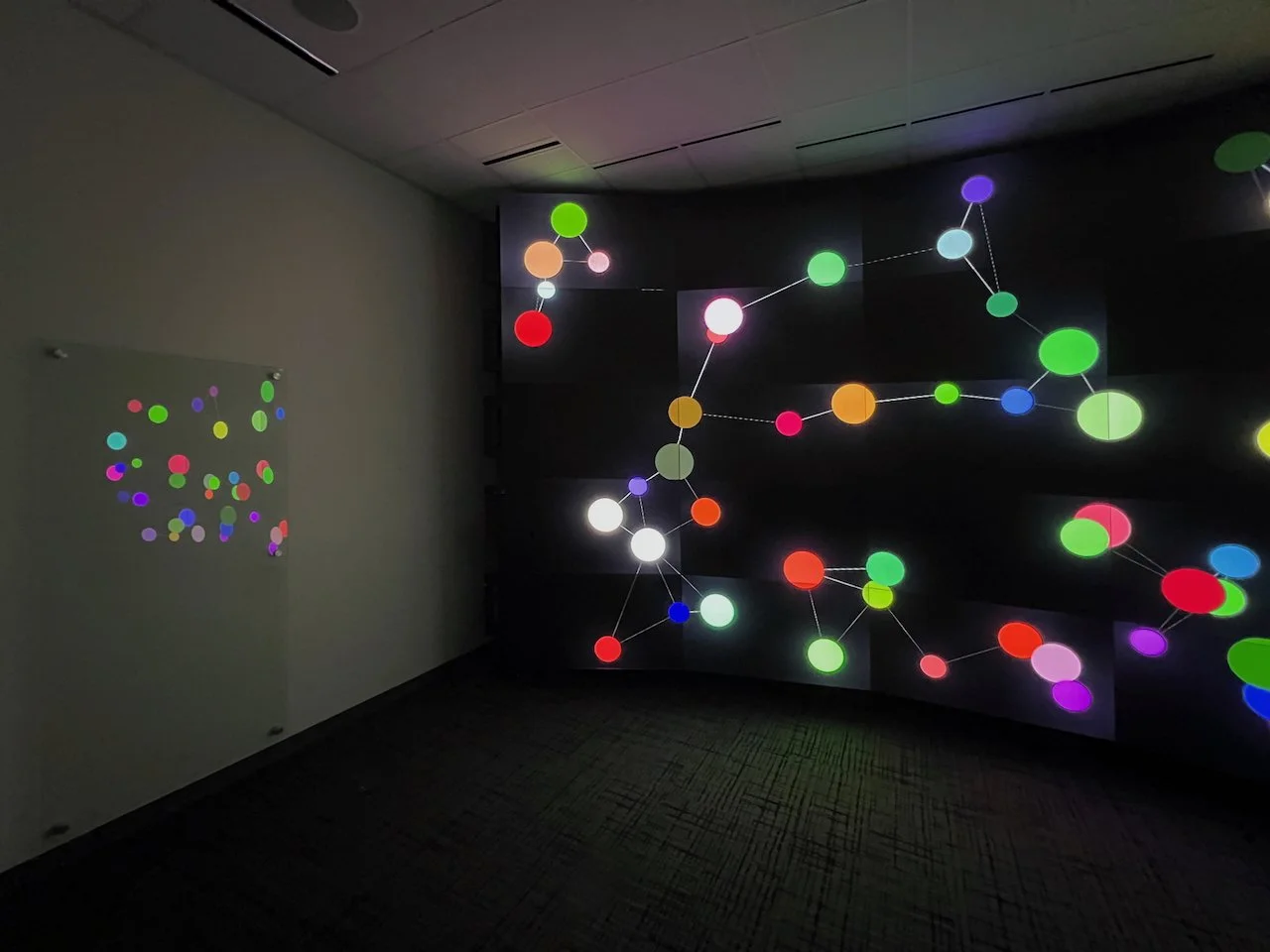

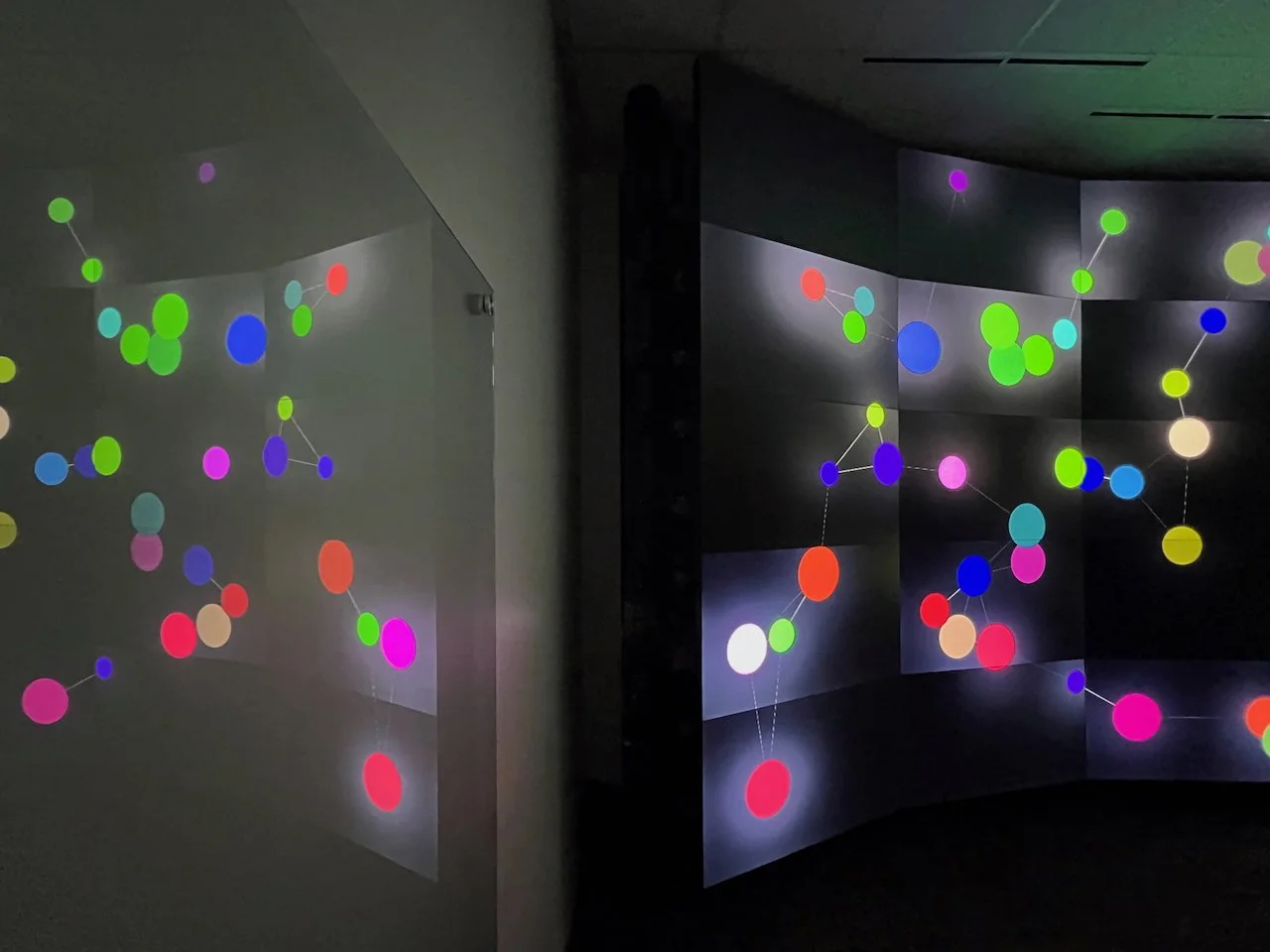

Part III: 68 Points

Stanford University, Stanford, California, USA, 2025

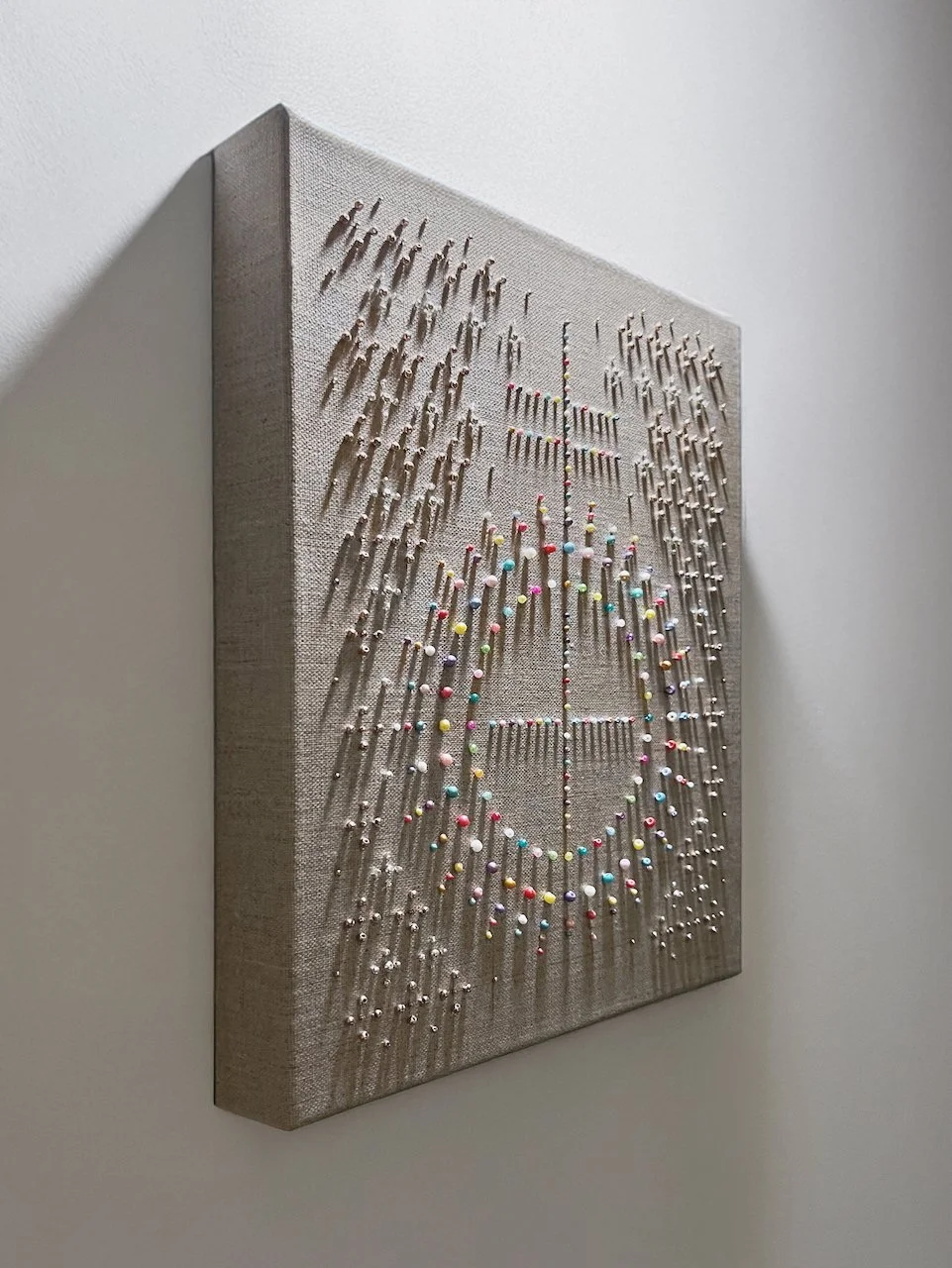

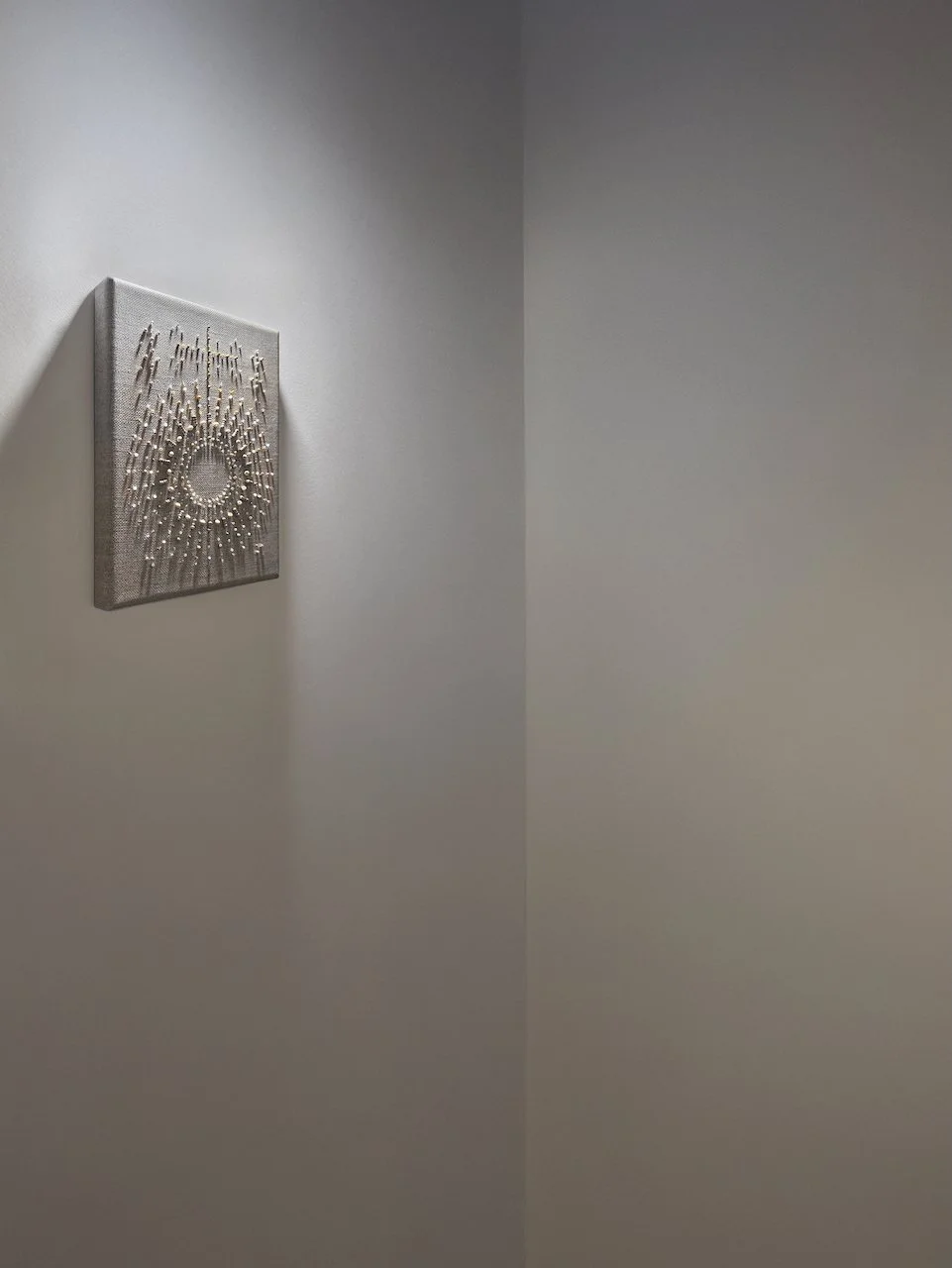

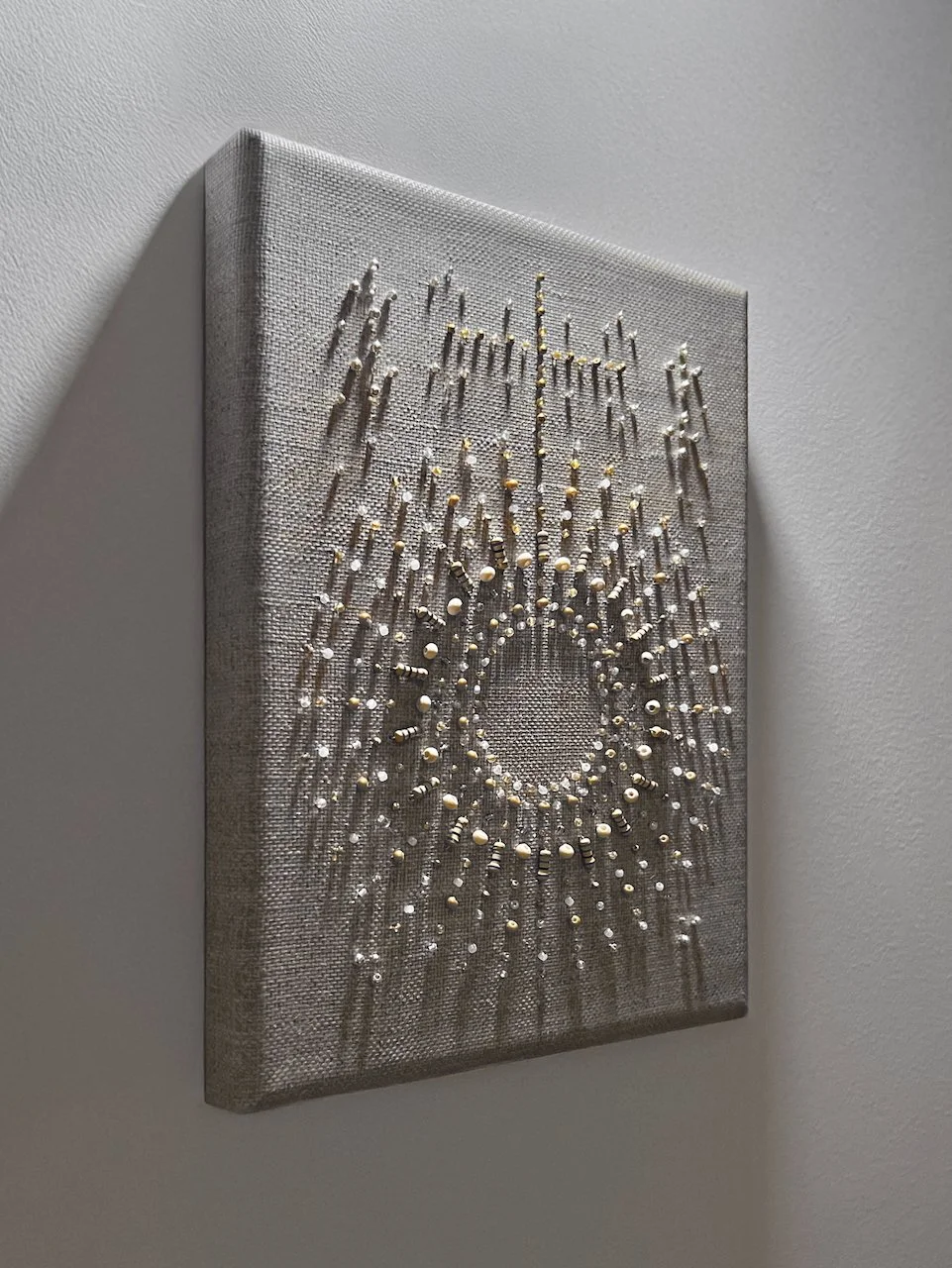

Some conversational AI agents embed facial recognition. These systems leverage advanced computer vision algorithms to identify and analyse human faces, commonly using 68 points (or facial landmarks) distributed across the face to capture key features. This enables them to personalise interactions based on a user’s identity, emotions, and/or demographic traits. Pepper, a humanoid robot on the market, uses facial recognition to interact with people in stores, hotels, and homes. Equipped with cameras and AI, it can detect faces, estimate age, estimate gender, and recognise emotions. Pepper might say, “Welcome back Sarah!” to a returning customer or offer comfort if it detects sadness, tailoring its conversation accordingly. There are increasing reports of “smart kiosks” using facial recognition to check people into hotels, authenticate access to bank accounts, and provide targeted recommendations. Although there are potential benefits regarding security, customer service, and healthcare, there are major concerns being raised about the threat to safety and privacy.

In 2018 a research report was published by researchers at Stanford University suggesting AI could analyse facial images and predict sexual orientation with notable accuracy, based on traits such as jawlines and nose shapes. This research highlighted a potential threat to queer communities regarding the use of AI based facial recognition to identify and report queer people to authorities. This potential threat became a reality in 2025 when the Government of Hungary passed law authorising facial recognition technology to identify participants at what the government deemed “unlawful” organised events like pride parades. Concerns have been raised over the use of this technology to systematically identify and report queer individuals to authorities, amplifying risks of harassment, arrest, or worse.

68 Points raises the alarm about the existing and future weaponisation of AI based facial recognition against queer communities worldwide, particularly those who live in countries where being queer is illegal. What are the dangers? What should we be doing to address concerns? Who should we engage?

Works will appear on campus virtually and physically at:

Stanford Art Gallery

Other indoor and outdoor sites on campus

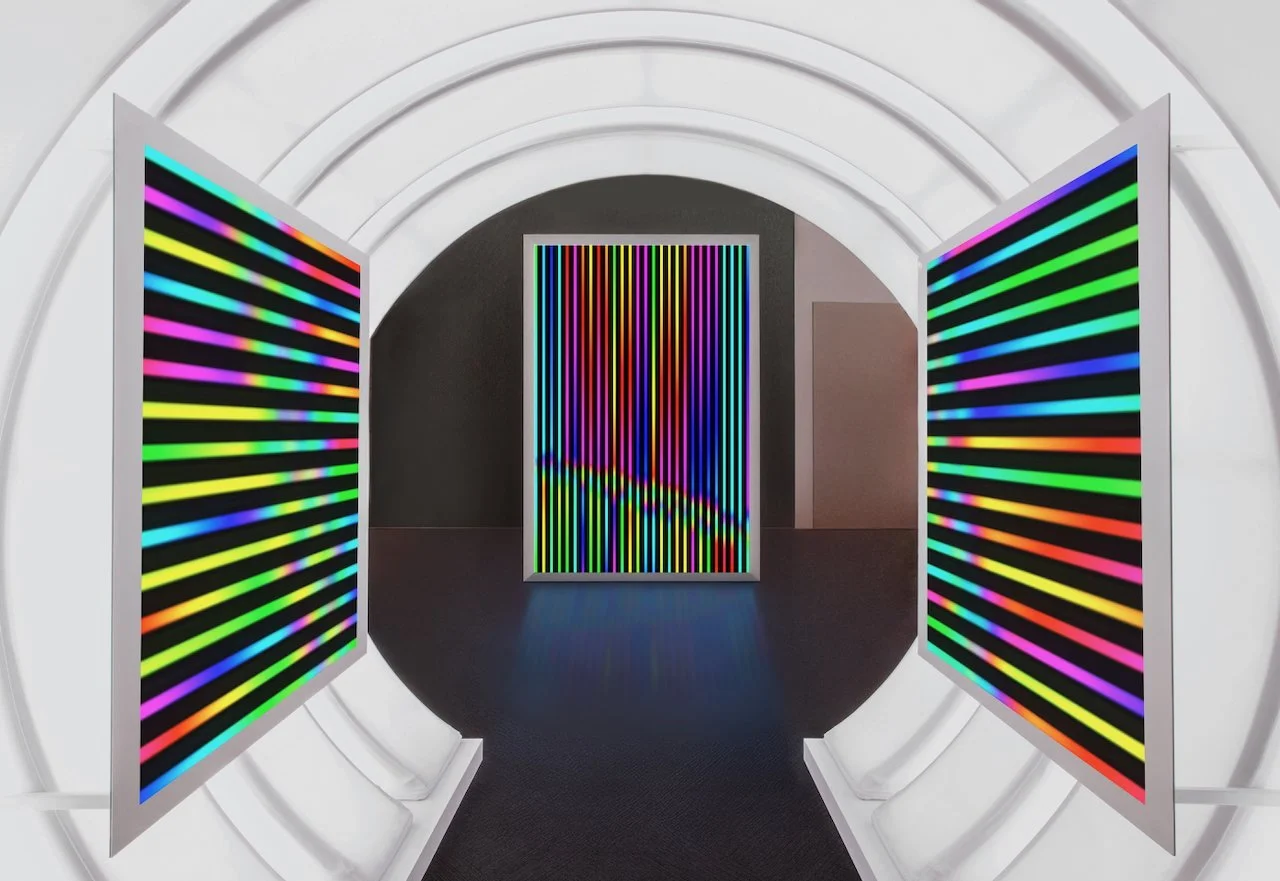

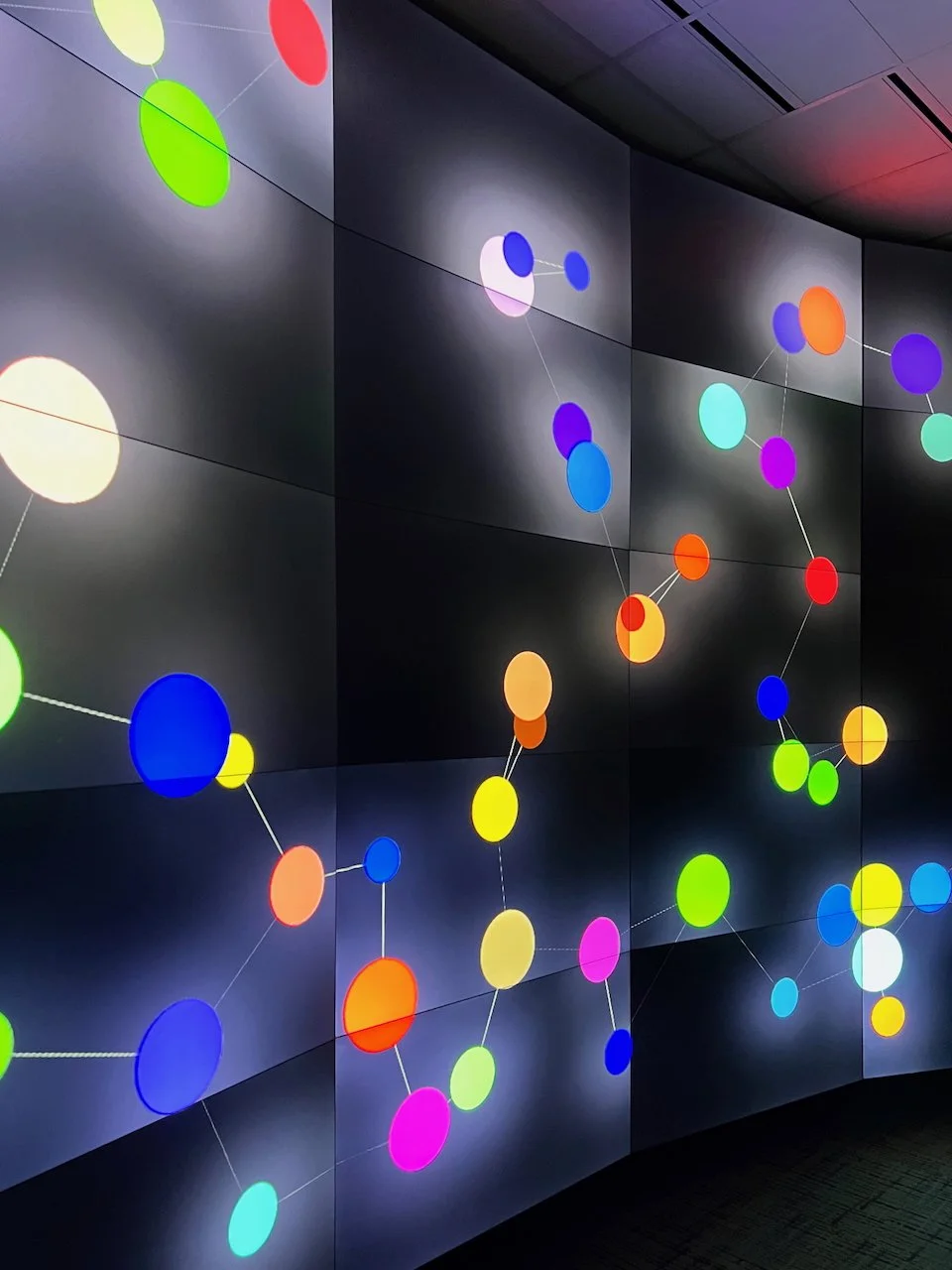

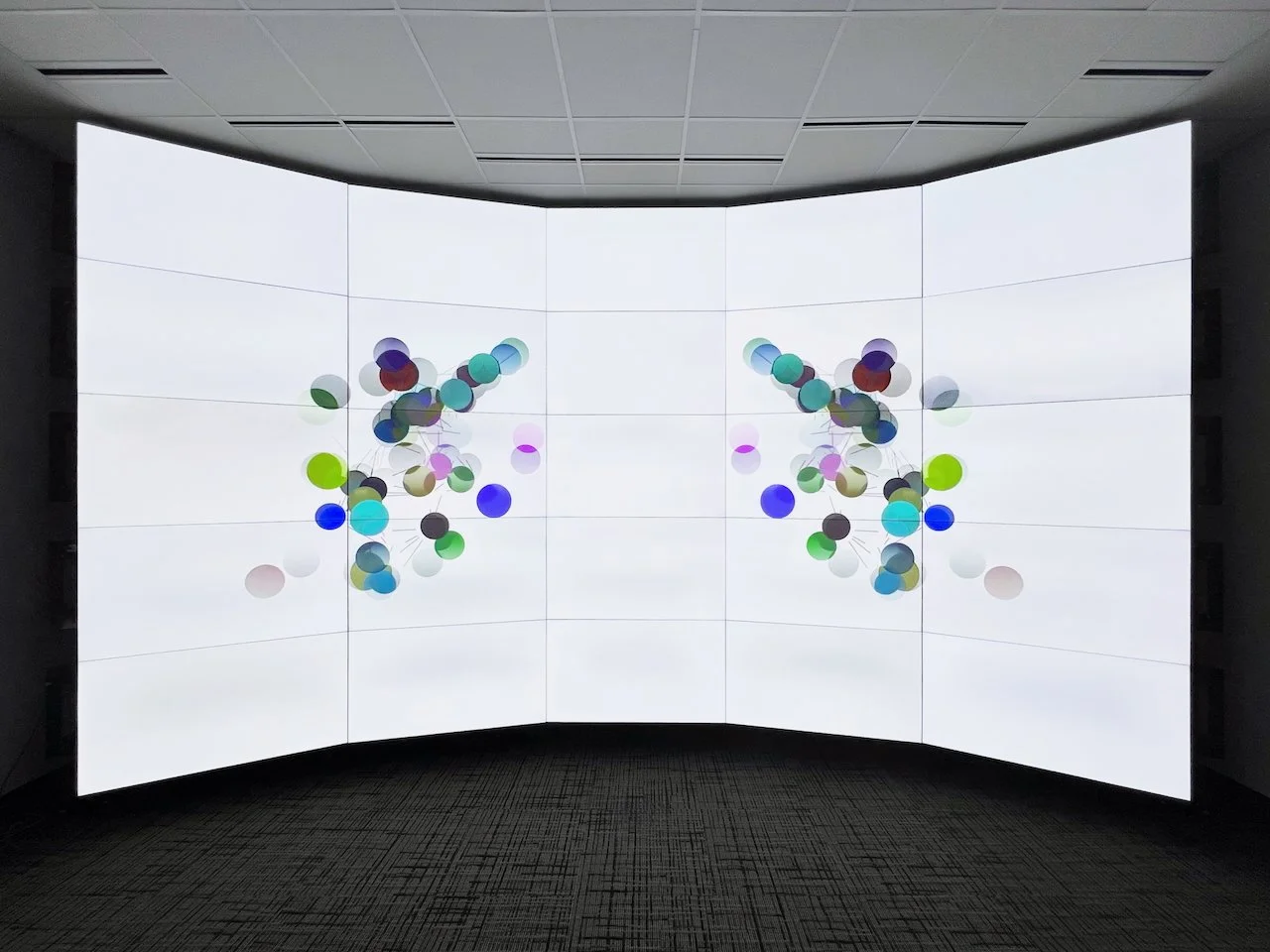

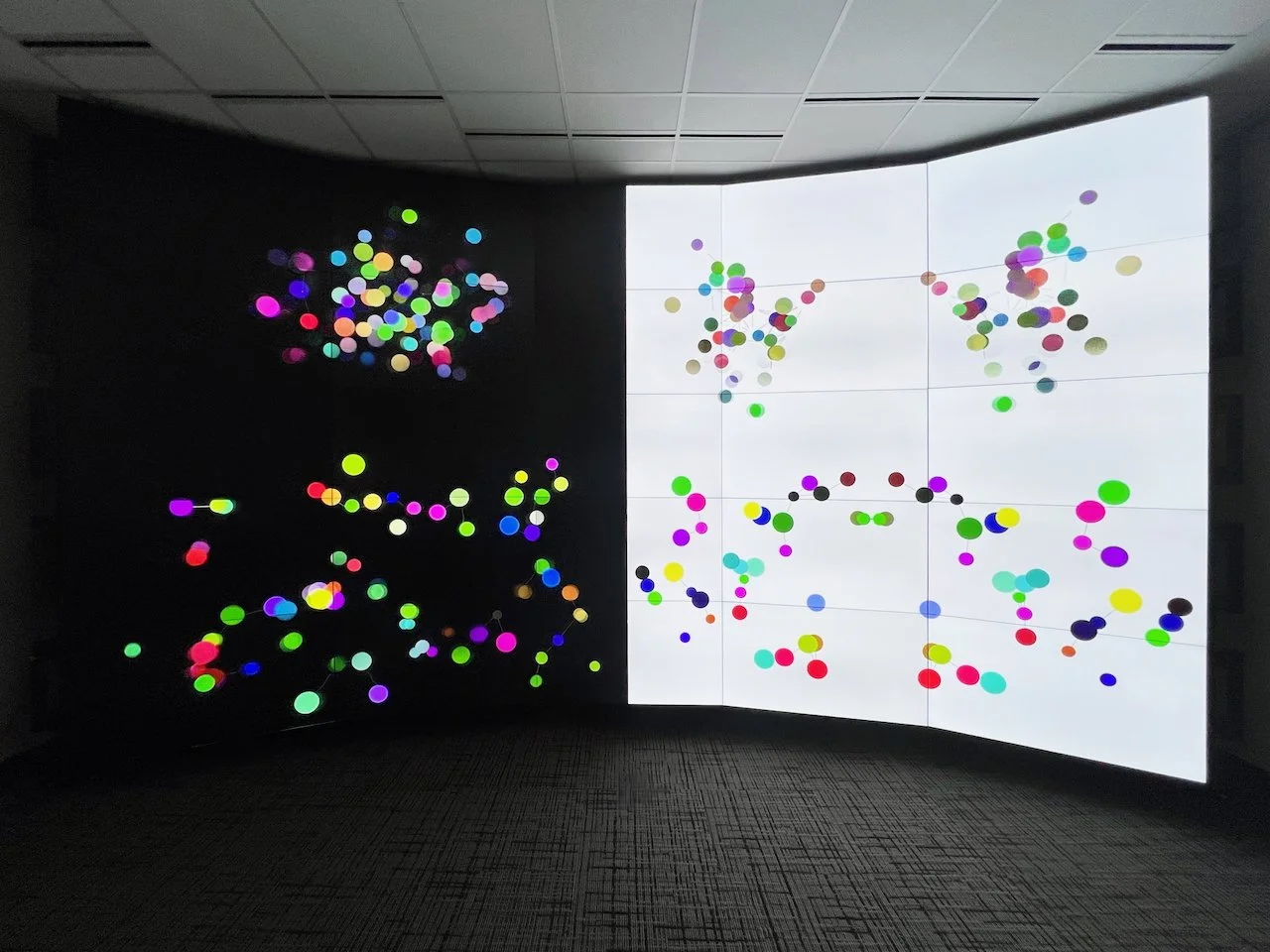

68 Points includes generative animation works, each made of 68 points (or landmarks) that explore and expose the weaponisation of AI-based facial recognition to analyse queer bodies in different ways. These were shown on campus using the HANA Immersive Visualisation Environment (HIVE).